Dowry, Personal Law, and Constitutional Morality: Reaffirming Core Principles in Dowry Death Jurisprudence

Introduction

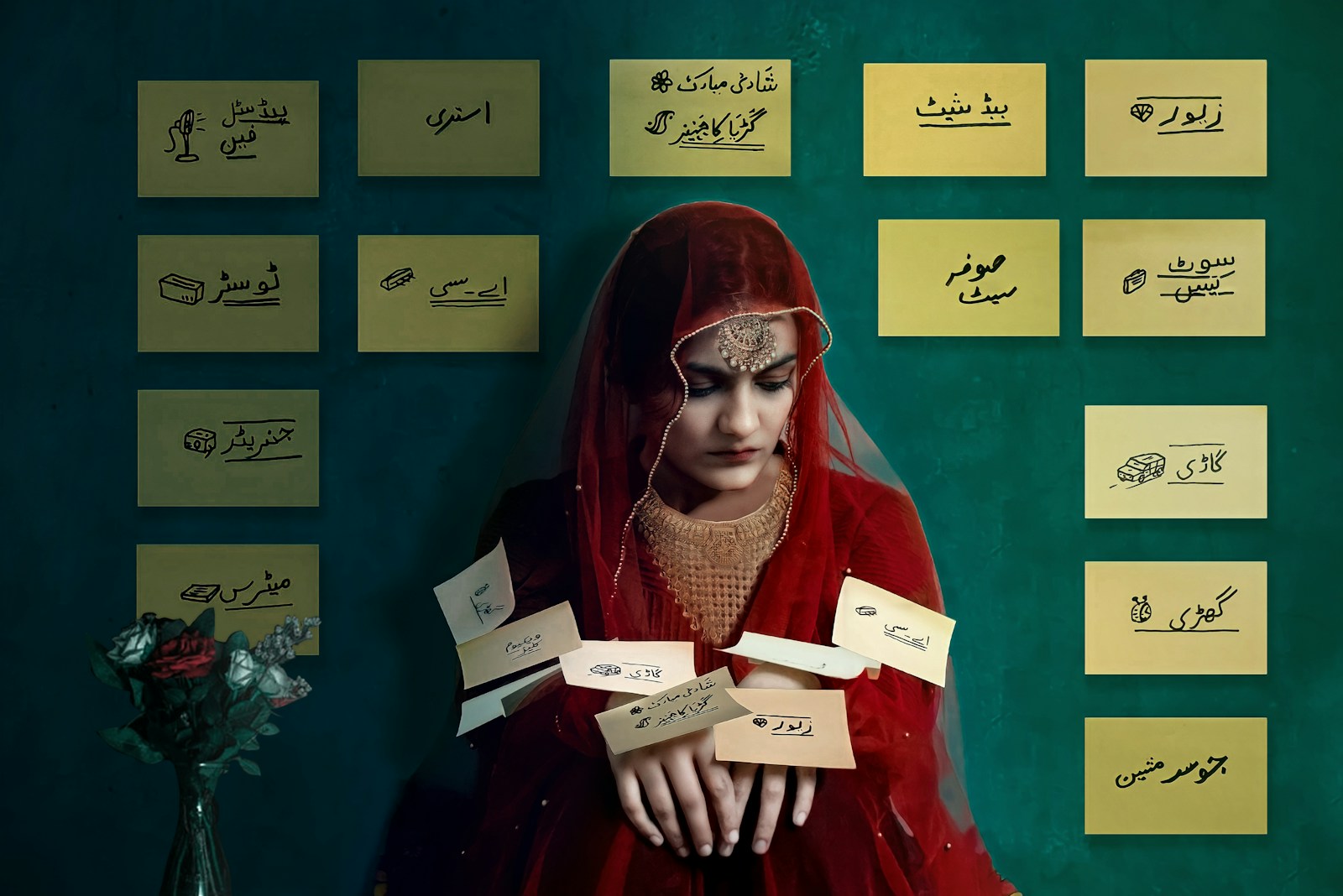

Dowry-related violence continues to be one of the gravest manifestations of structural inequality faced by married women in India. Despite decades of legislative intervention, the practice of dowry persists often disguised as custom, tradition, or voluntary gifting frequently culminating in cruelty, harassment, and in extreme cases, death. Recognising this entrenched social reality, Parliament enacted a stringent legal framework through the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, Sections 498-A and 304-B of the Indian Penal Code, and the evidentiary presumption under Section 113-B of the Indian Evidence Act.

In State of Uttar Pradesh v. Ajmal Beg & Anr.1, the Supreme Court undertook a comprehensive re-examination of these provisions, reaffirming the doctrinal foundations governing dowry offences and correcting a troubling dilution of settled principles by the High Court. The judgment is significant not merely for restoring a conviction in a dowry death case, but for its clear articulation of dowry as a constitutional wrong, its insistence on a purposive interpretation of anti-dowry statutes, and its emphasis on the mandatory nature of statutory presumptions designed to protect vulnerable married women.

This decision thus serves as an important restatement of law on dowry, cruelty, and dowry death clarifying evidentiary thresholds, reinforcing the social purpose of penal provisions, and underscoring the judiciary’s role in confronting deeply rooted discriminatory practices that undermine the constitutional guarantees of equality, dignity, and life.

Table of Contents

Statutory Framework Governing Dowry and Cruelty

India’s response to dowry-related offences is embedded in a composite statutory scheme comprising the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, Sections 498-A and 304-B of the Indian Penal Code, and Section 113-B of the Indian Evidence Act. The Supreme Court reiterated that these provisions must be read harmoniously and purposively, as instruments designed to address a pervasive social evil rather than as isolated penal clauses.

Definition of Dowry under the Dowry Prohibition Act

The Court reaffirmed the expansive scope of “dowry” under Section 2 of the Dowry Prohibition Act, holding that any property or valuable security demanded or given before, at, or any time after marriage, provided it has a nexus with the marriage, constitutes dowry. The timing of the demand is immaterial. Post-marriage demands, often normalised as expectations or necessities, fall squarely within the statutory prohibition.

The Court firmly rejected arguments seeking to characterise dowry as voluntary or customary gifting, emphasising that social acceptance cannot legitimise an unlawful demand.

Cruelty under Section 498-A IPC -Husband or relative of husband of a woman subjecting her to cruelty

Section 498-A IPC was recognised as a standalone and preventive provision addressing sustained mental and physical cruelty within marriage. The Court clarified that cruelty under this section is not confined to dowry death scenarios. Harassment intended to coerce unlawful demands or conduct causing grave psychological harm independently attracts criminal liability, highlighting the provision’s role in intervening before cruelty escalates into fatal violence.

Dowry Death under Section 304-B IPC

Section 304-B IPC addresses deaths of married women occurring under unnatural circumstances within seven years of marriage, where dowry-related cruelty is established. The Court reiterated that the offence is deemed in nature, and once statutory ingredients are satisfied, culpability is legally presumed unless rebutted.

A key clarification concerned the phrase “soon before her death.” The Court held that this expression does not require immediate proximity but demands a reasonable and live link between dowry-related harassment and the death, assessed contextually.

Presumption under Section 113-B, Evidence Act

Recognising the evidentiary challenges inherent in crimes occurring within domestic spaces, the Court reaffirmed that the presumption under Section 113-B is mandatory, not discretionary. Once dowry-related cruelty shortly before death is shown, the burden shifts to the accused. Failure to rebut this presumption strengthens the prosecution case.

Background of the Case

The case arose from the death of a young married woman within a short period of her marriage, allegedly on account of persistent dowry-related harassment. The deceased was married to Ajmal Beg and had been residing in her matrimonial home along with her husband and his family members. The marriage had taken place barely a year prior to the incident.

According to the prosecution, soon after the marriage, the deceased was subjected to repeated demands for dowry by her husband and his relatives. These demands included a colour television, a motorcycle, and a cash amount of ₹15,000. The deceased allegedly communicated these demands and the accompanying harassment to her parental family on multiple occasions during visits to her natal home. The family expressed their inability to meet these demands due to financial constraints.

It was further alleged that the demands were reiterated shortly before the incident. On the day preceding her death, the husband is stated to have renewed the demand for dowry, despite being informed that the deceased’s family was incapable of fulfilling it. The next day, the deceased was found dead in her matrimonial home, having suffered extensive burn injuries.

An FIR was lodged by the deceased’s father, following which an investigation was conducted. Upon completion of the investigation, charges were framed against the husband and certain family members under Sections 498-A and 304-B of the Indian Penal Code, along with Sections 3 and 4 of the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961.

The Trial Court, after evaluating the evidence and witness testimonies, convicted the husband and his mother, holding that the prosecution had successfully established continuous dowry demands, harassment, and that the death occurred within seven years of marriage under unnatural circumstances. Other accused family members were acquitted on the ground that their involvement was not proved beyond reasonable doubt.

On appeal, the High Court reversed the conviction and acquitted the accused, primarily on the basis of perceived inconsistencies in witness testimonies, doubts regarding the credibility of prosecution witnesses, and assumptions relating to the socio-economic status of the accused.

Aggrieved by the acquittal, the State of Uttar Pradesh approached the Supreme Court. The appeal required the Court to examine whether the High Court had erred in disregarding settled principles governing dowry death, statutory presumptions, and appreciation of evidence in cases involving offences committed within the matrimonial home.

Findings of the Courts

Trial Court

The Trial Court found consistent evidence of dowry demands and harassment “soon before” the deceased’s death. Medical evidence confirmed that the death occurred under unnatural circumstances. Applying Section 113-B of the Evidence Act, the Court held that the accused had failed to rebut the presumption of dowry death and convicted the husband and his mother.

High Court

The High Court overturned the conviction by adopting a hyper-technical approach to evidence, emphasising minor inconsistencies, absence of eyewitnesses, and assumptions regarding the accused’s economic capacity. It also relied on selective statements suggesting marital harmony to discredit the prosecution case.

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court held that the High Court’s approach was legally unsustainable. The decision in State of U.P. v. Ajmal Beg & Anr. serves as a restatement of settled yet frequently diluted principles governing dowry-related offences. The Supreme Court reaffirmed the following core doctrines:

1. Dowry Is a Broad and Inclusive Concept

Dowry is not confined to demands made at the time of marriage. Any demand for property or valuable security made before, at, or after marriage, so long as it is connected with the marriage, falls within the statutory definition under the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. Courts must guard against attempts to re-characterise dowry as “customary gifts” to evade liability.

2. “Soon Before Her Death” Requires a Reasonable Nexus

The expression “soon before her death” under Section 304-B IPC does not mandate immediate temporal proximity. What is required is a reasonable and live link between dowry-related cruelty and the woman’s death. A demand reiterated even a day prior to death clearly satisfies this requirement.

3. Presumption under Section 113-B Is Mandatory

Once it is shown that a married woman was subjected to dowry-related cruelty soon before her death, the presumption of dowry death must be drawn. This presumption is statutory and shifts the burden of proof onto the accused. Failure to rebut it through evidence strengthens the prosecution case.

4. Minor Inconsistencies Do Not Discredit the Prosecution

Dowry death cases arise within the private sphere of the matrimonial home. Minor contradictions, omissions, or emotional inconsistencies in witness testimony are natural and cannot override a consistent core narrative. Courts must separate trivial discrepancies from material contradictions.

5. Financial Status of the Accused Is Legally Irrelevant

The Court rejected the notion that dowry demands can be disbelieved based on the accused’s poverty or inability to maintain demanded articles. Such assumptions are speculative and have no place in judicial reasoning under dowry laws.

6. Section 498-A IPC Has an Independent and Preventive Role

Cruelty under Section 498-A IPC is not limited to dowry death. Sustained harassment, mental cruelty, or coercion related to unlawful demands independently attracts criminal liability, reinforcing the provision’s preventive purpose.

7. Acquittals in Social Offence Cases Require Judicial Restraint

Appellate courts must exercise caution while overturning well-reasoned convictions in dowry cases. Reversal is unwarranted unless findings of the trial court are shown to be perverse, illegal, or wholly unsupported by evidence.

8. Sentencing Must Balance Justice with Humanitarian Considerations

While culpability cannot be erased, sentencing may consider age and physical condition of convicts. Humanitarian considerations may mitigate punishment without undermining the finding of guilt.

Dowry, Personal Law, and the Clarification on Mehr

A notable contribution of the judgment is its clarification on the relationship between dowry law and personal law, particularly mehr under Muslim law. The Court categorically held that mehr, a mandatory marital obligation meant to secure the wife’s financial rights cannot be equated with dowry, nor can its payment be used as a defence to negate dowry demands.

The Court emphasised that dowry is a coercive demand imposed on the woman or her family, whereas mehr is a legal right of the woman. The existence of mehr does not legitimise post-marriage demands for property or money. Secular criminal law governing dowry applies uniformly, irrespective of religion, and personal law concepts cannot be invoked to dilute statutory protections.

Directions for Institutional Strengthening and Social Reform

Beyond adjudication, the Court acknowledged the persistent failure of dowry laws due to weak enforcement and social acceptance of the practice. Accordingly, it issued a series of mandatory and advisory directions aimed at long-term reform:

Educational Reform

The Court directed the Union and State Governments to consider integrating constitutional values of gender equality and anti-dowry awareness into educational curricula, recognising that legal deterrence alone is insufficient without social transformation.

Activation of Dowry Prohibition Officers

Emphasising Section 8-B of the Dowry Prohibition Act, the Court directed States to ensure effective appointment, training, and public visibility of Dowry Prohibition Officers, including dissemination of their contact details at the local level

Training of Police and Judicial Officers

The Court stressed the need for regular sensitisation programmes for police and judicial officers to enable them to distinguish genuine dowry cases from misuse, while maintaining empathy for victims of domestic cruelty.

Expeditious Disposal of Pending Cases

Acknowledging prolonged delays in dowry death trials, the Court called upon High Courts to review pendency of cases under Sections 304-B and 498-A IPC and ensure time-bound disposal, particularly of older matters.

Grassroots Awareness through Legal Services Authorities

The Court directed District Administrations and Legal Services Authorities to conduct awareness programmes, especially targeting populations outside the formal education system, thereby addressing dowry as a grassroots social issue rather than merely a penal offence.

Significance of the Court’s Approach

What distinguishes this judgment is its recognition that dowry-related crimes cannot be addressed solely through post-facto punishment. By combining strict doctrinal enforcement with institutional and societal directives, the Court reaffirmed its constitutional role as both adjudicator and catalyst for social reform.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision in State of U.P. v. Ajmal Beg & Anr. stands as a reaffirmation of the judiciary’s commitment to confronting dowry as a systemic and constitutionally impermissible practice. By restoring the trial court’s conviction and correcting the High Court’s dilution of settled principles, the Court reinforced the purposive interpretation of anti-dowry statutes and highlights the mandatory nature of statutory presumptions crafted to address crimes committed within the secrecy of the matrimonial home.

The judgment clarifies that dowry demands cannot be trivialised by social custom, economic assumptions, or selective appreciation of evidence. It reiterates that minor inconsistencies in testimony do not eclipse a consistent narrative of cruelty and harassment, and that appellate courts must exercise restraint while interfering with convictions in social offence cases. Importantly, the Court balanced doctrinal rigor with humanitarian sentencing considerations, demonstrating that compassion in punishment does not equate to exoneration of guilt.

Beyond the immediate facts, the judgment carries broader significance. By issuing systemic directions aimed at education, enforcement, judicial sensitisation, and grassroots awareness, the Court acknowledged that dowry eradication cannot be achieved through penal sanctions alone. The decision thus situates dowry law within the larger constitutional project of ensuring dignity, equality, and substantive justice for women.

In reaffirming that marriage cannot be a site of economic coercion or violence, the Supreme Court has strengthened the legal and moral foundations of India’s anti-dowry framework reminding courts, institutions, and society alike that the promise of constitutional equality must extend into the most private spaces of social life.

For more details, write to us at: contact@indialaw.in

By entering the email address you agree to our Privacy Policy.